-

- “One of the things that we say in

Steeltown

- , and that John Russo and I have been saying even more in the last two years since this ‘great recession’ started, is that Youngstown’s story is America’s story.” -Sherry Linkon

Dr. Sherry Linkon is a Distinguished Professor of English and American Studies at Youngstown State University. She is the co-director of YSU’s Center for Working Class Studies and the co-author of Steeltown USA: Work and Memory in Youngstown. Beyond these, Dr. Linkon is a prominent social activist and the coordinator of the Steel Valley Voices archive, an online collection of stories and photographs of the Mahoning Valley.

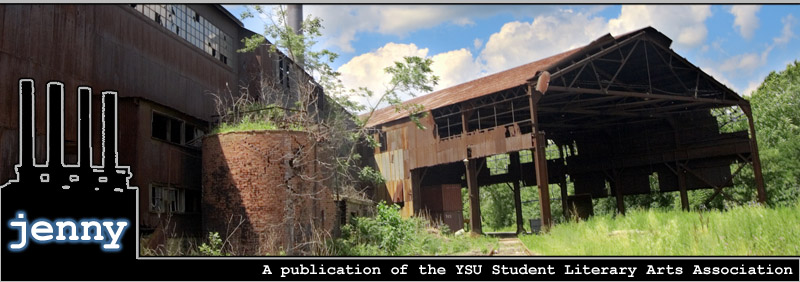

For our inaugural issue of Jenny, we were very fortunate to have the opportunity to sit with Dr. Linkon to discuss a great variety of subjects: Youngstown’s connection to the world as a characteristic tale of industrialization; the city’s continuing role in a less industrial America; the importance of arts and literature in the rustbelt and in Youngstown in particular.

An Interview with Sherry Linkon

Click to listen:

http://archive.jennymag.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/A-Moment-with-Sherry-Linkon.mp3

TRANSCRIPT:

Chris: Hi everyone. This is Chris Lettera here for Jenny speaking with Dr. Sherry Linkon. Sherry currently teaches at Youngstown State University. She is also co-director of the Center for Working Class Studies here at Youngstown State, and she is co-author along with John Russo of Steeltown USA: Work and Memory in Youngstown. Sherry, thanks for being here today. So, we’re taking work from anyone with Jenny. We’re publishing prose – fiction and creative nonfiction – and we talked early on how if you make anything in Youngstown, particularly a literary magazine, you can’t escape the fact that it’s being made here. You talked about in Steeltown, how place is a means of identity and defining self. One of our goals is to connect Youngstown to the world and the world to Youngstown. Can you describe Youngstown for someone who maybe hasn’t visited the city?

Sherry: Well, let me start with this. One of the things that we say in Steeltown and that John Russo and I have been saying even more in the last two years since this “great recession” started is that Youngstown’s story is America’s story. That is, what happened in Youngstown, which is essentially the history of industrialization, incredible growth in a community because of one big industry… and then incredible struggle when that history shut down. And while I think it’s important for people to understand that we still do make steel here, and we still do work with all kinds of specialty metals, that’s a much smaller industry and it has really dramatically reshaped this place. So, somebody who hadn’t been here looking at this landscape… the thing they would notice most, probably, is all of the flaws in the landscape. You know, they would see the empty lots both in residential neighborhoods and along the Mahoning Valley where the steel mills once stood. They would see that there are businesses boarded up in various places. They wouldn’t necessarily recognize what all was going on behind that, and I think one of the reasons that it’s so important for people to create visual art and write stories and poems and songs and play and whatever they do about Youngstown and places like this is that there is so much more going on than just loss.

Chris: Right.

Sherry: But that’s the story that so often gets told.

Chris: Yeah, so much of it seems image-based. There was a national story in ESPN recently about Kelly Pavlik, the former middleweight champion from Youngstown, and they showed an image of Youngstown Sheet and Tube and it looked pretty decrepit, so it’s interesting how, you know, it’s really a post-steel place at the moment. You wrote in Steeltown that how Youngstown remembers its past plays a central role in how it envisions its future. Steeltown was published back in 2002. How is Youngstown doing at remembering now.

Sherry: Much better. I’m pleased to say I wish I could claim that’s because of what we wrote. I’m not sure I can make that argument (laughs). I think a couple of thigns have happened. Much of it has to do with the fact that there is now a younger generation that grew up after the steel mills closed for whom the loss associated with that is every bit as important as it was to their parents and grandparents but is somewhat less painful. And so it’s a little bit easier for them to talk about. And what I see coming out of that generation is a lot of creative work, some political work, some community organizing… that reflects a respect for the history of the community, as opposed to what we once saw which was the idea that we should just forget the past. So a lot of people now are saying, “You know, I get it. The past shaped this place. We have to come to terms with that.” And if we do that, we can create a better future. So they’re working in neighborhoods and trying to draw on the fact that people have lived there for fifty years and have a deep sense of what that area is about. That becomes a tool for making things happen to improve the quality of life in this community. I see the same thing happening with the kinds of creative writing and photography and images that people are making.

Chris: It’s interesting in speaking to a lot of my fellow students how many of us have had parents or grandparents who have worked in the steel industry here and how we’re trying to bridge that gap and not make it a disconnect. The Center for Working Class Studies began in 96 and its notable for being the first academic program in the US to focus on issues of work and class. Can you tell us a little more about how the Center began?

Sherry: We got started out of two different things. First of all, we had a cluster of faculty in English, Art, and Labor Studies, and History, who were interested in the role that this community played in twentieth century American history. And so in 1992, we sponsored a conference on the 1930s, and that brought us together as kind of an organizing team. But the other thing that happened was, because we were talking about the 1930s which was the Great Depression, a lot of people were talking about worker and the organizing, the labor movement that in 1937 was a key point in the history of the labor movement, and much of that centered around Youngstown… The Little Steel Strike, and the recognition of the first steelworkers unions. And people kept saying to us, “This is great! We never get together to talk with people who care about these issues! You guys oughta do this again.” And so part of this started with conferences, and in 1995 we held the first conference we called a “working class studies conference,” which felt like a gathering of orphans. You know, all of these people coming from all across the country saying, “No one on my campus cares about class. Here, I get together and talk with other people who care about it.” So that was one thread. The other was… the nineties were a period when a lot of work was going on in college campuses around multiculturalism, largely in the humanities but also some in the social sciences. And most of that conversation was about race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality. Nobody was talking about class although class is embedded in all of those things. So we wrote a grant application to a national project on transforming the curriculum asking, “Will the working class be invited to the diversity banquet?” Literally, they called us the day after they got the application and said “Oh my god! You’re right. Nobody’s talking about this. You guys have to be here.”

Chris: Yeah.

Sherry: That gave us the leverage with the university to say, “People elsewhere agree with us that this matters. We’re gonna do some curriculum projects, we’re gonna do some work with the local community, we’re gonna do some research.” And the provost at the time gave us money with one stipulation. He said, “You gotta get other faculty involved.” He said, “There’s five of you to start with. Your job…” He said, “I’ll keep funding you if you can come back in a couple years and show us that there are other people on campus who care about this.” So that was one of our primary tasks over the next few years.

Chris: I was looking at the website, and the Center for Working Class Studies lists one of its goals as being to “promote awareness and appreciation for writing, art and other creative expressions of working class experience.” You mentioned earlier what we could learn from these things. Can you tell me about anyone specific? Can you tell me about Bryn Zellers, for example?

Sherry: I love to talk about Bryn Zellers (laughs). Bryn is sort of one of my creative heroes. I first met Bryn in the early nineties as he was beginning to do work actually for the Center. As we were just getting started, he designed some posters for us, and part of what I appreciated about his work is that he did something a lot of other people – especially visual artists – were not doing. There’s a ton of visual work about American industry that focuses on the machinery, the buildings, structures. There’s very little that puts human beings in them. But, part of my philosophy about understanding industrialization and deindustrialization is about how important it is for people’s lives. Almost everything Bryn has ever designed for us, and a huge part of the work he does on his own makes human beings present. He’s thinking all the time about, “What is this about people?” So if you come down to the Center for Working Class Studies, in the hallway at Smith Hall, we have the series of posters that Bryn designed for our conferences. We did seven conferences between 1992 and 2005, and we commissioned him to design a poster for every one which we handed out to people who registered for the conference and we’ve taken them all around the world. So Bryn’s work is in fact in faculty offices, at least, and museums – not necessarily on the walls of the museum but in somebody’s office in the museum – all around the world. And they all have both, the equipment and the spaces of industrial work and of the community, and people. And that, to me, that’s part of what makes his work so fascinating. The other thing I find so fascinating about Bryn is that he has a clear understanding of why all of this history matters even though he didn’t live it himself. You know, he ironically didn’t become a steelworker until sometime in the last five years.

Chris: (laughs)

Sherry: You know, now he works with steel. You know, not making sculpture, but making, fabricating… you know, whatever it is he fabricates. I don’t actually know these days what he’s making.

Chris: (laughs)

Sherry: But he grew up near it. It was all around him. And he’s therefore a very good example of how living in this kind of place can shape you even if you don’t work in it directly.

Chris: Right, yeah. Yeah, art as a means of connection sort of. It’s interesting. We went down to the Mahoning Valley Historical Society recently to look at some images of Jenny and some of the blast furnaces and the one notable thing was the absence of the human form. It was all, like you said, focused on the machinery and one of the things we’re trying to do with Jenny is channeling the human energy and human spirit involved in this production. That’s where we got our name from. Uh, I don’t think it was actually called Jenny until Bruce Springsteen wrote his song…

Sherry: You know, there’s some argument about that, because as we were doing… like, I know Rick Rowlands for example, makes the claim very strongly that nobody called it the Jenny. But as we started to go out and do interviews with people who lived in that neighborhood, we heard people using that term. So, whether that happened because people had heard about Springsteen’s song, you know, I can’t trace that.

Chris: Right.

Sherry: But, certainly it’s a powerful way of thinking about it whether people used that term or not, in part because we know that both writers and artists talking about the steel, about steelmaking, have used images of sexuality, and images of a kind of romance in doing that. There are some wonderful poems by a writer named Patricia Dobler. They’re set sort of between the 1890s and all the way up to I think the 1970s based on her own family’s interaction with the steel mills. And there’s this beautiful piece talking about returning to the mill after a long strike in the 1950s. And the steel industry in the fifties was consistently… there were lots of strikes. And somebody is returning to the mill after a strike, and the sense of desire of entering… There’s a line, I may not quote it exactly right, but it talks about entering the mill like entering a woman’s body. You know, so to the chorus of that song, Springsteen’s song – “My sweet Jenny, I’m falling down,” that fits with that imagery so well.

Chris: Right. Yeah. If it’s ok, I wanted to read a little bit from Steeltown here. Again, Springsteen released the song “Youngstown” in 95 on the album “The Ghost of Tom Joad.” You wrote in Steeltown, “The chorus is addressed to “my sweet Jenny,” not a woman but a blast furnace, the Jeanette Blast Furnace at Youngstown Sheet and Tube’s Brier Hill Works. Like most steel mills in the area, the Brier Hill works closed at the end of the 1970s, but while most mill structures were torn down in the 1980s, the Jenny remained standing until 97, one of the few markers of the community’s past as one of the steelmaking capitals of the United States.” Again, coming from someone who never saw the Jenny, as far as I can remember, what did Jenny mean to somebody who worked there?

Sherry: Wow. Um, I think the structures of the steel mills had two meanings for people. One is simply about the connections they had with the other people they worked with. The primary thing that people say when they lose that kind of job, the number one thing they’re gonna miss is not the work itself… you know, we can never forget that the work in steel mills was hot, dirty, dangerous, unpleasant work. This is not a job you go to because you love shoveling coal into a big vat. But the connections, and the sense that the work you’re doing matters, that’s what’s important. And so on one hand, the structure represents all those connections. On the other hand, I think it represents… who we are. I think for a lot of people, it’s… it’s the reminder. Bryn said something in an interview about how, you know, when you tear it down, you erase part of history. They tore down most of the big steel mill buildings in Youngstown pretty quickly after the mills closed down, partially I think to… to make very clear that, you know, it’s not coming back. But I think that loss… those structures were a symbol. There’s a sociologist named Bob Bruno who wrote a book on Youngstown called Steelworker Alley, and one of the things he argues is that the steel mills were such large structures that occupied such a central space in the community… that people couldn’t believe they would ever go away. So, to then turn around and tear it down, that’s destroying the things that were so much at the heart of people’s lives, and they were symbols for what this place is. And the very fact that you guys are calling the magazine Jenny reminds us of how important it is, and it’s still important, even though it’s been gone for more than ten years.

Chris: Yeah, it’s a ghostly image. We looked at a lot of photographs of it and really, really been moved by it and what it means to previous generations, to us, to our future. I spoke with Rick Rowlands yesterday. His Tod Engine Heritage park is about eight minutes from my house on Old Hubbard Road. It’s a 1.2 acre site that houses historic steelmaking equipment from the region. Back in 96, Rick led an effort to preserve the Jenny blast furnace, and one of the things he told me yesterday was that… that if the interest in that type of history existed back then as it does now, that the Jenny may still be standing. And I know with the Steel Museum here and Mahoning Valley Historical Society, there’s a great emphasis on the history but… I guess as a student, I’m interested when people talk about the Youngstown Renaissance… is there a renaissance going on? Is there a renaissance for a select part of the city? Downtown? The neighborhoods? Can you talk a little about that?

Sherry: Sure. I think there is a renaissance going on. I think there is… there are some really interesting examples of both economic growth and growing of… I’ll use some jargon here… kind of social capacity, that is, networks that make it possible to actually do something effective. The problem with that is that… it leaves out a lot of the city. And this is the tension within that same group of people I was talking about earlier who understand the value of the history of the place and want to work harder to make it a better community. For some of them, that gets defined almost entirely around developing downtown. Now, there’s no doubt, if you go to downtown Youngstown, there’s a renaissance going on. John Slanina, who does the blog Shout Youngstown, said to me in an interview a couple of years ago something that has really changed my way of thinking about Youngstown. He said, “You know, Sherry, I was born in 1977. I was born two months after the first major closing was announced. Downtown Youngstown now is the best I’ve ever seen it.” I said, “You know, John, you’re right. I moved her in 1990, and I see that difference. On the other hand, the neighborhoods where many of us lived, and not only the neighborhoods that have been struggling with poverty for thirty years, but neighborhoods that were once, you know, pretty solid. We’re facing a whole lot of problems. We’re seeing crime increasing. You know, there’s an empty house that I walk past every morning when I walk my dog, and I keep thinking, “You know, twenty years ago, that place would have been snapped up, and somebody would be taking care of it.” So we have a real contradiction going on. We do have growth and I want to celebrate that growth. On the other hand, I don’t want to put blinders on and pretend that growth makes everything wonderful.

Chris: Absolutely. Yeah, it takes an honest approach. And you talked about passing that house every morning. I know… part of the student experience, I mean, we have a lot of students that live off campus, and just myself driving into campus every day and seeing the city and seeing various buildings in various states of disrepair, but also, you know, the historic district off of Fifth Avenue. Beautiful homes. There’s this duality in image and condition around the city. Again, going back to students, can you talk about some of the classes you teach here at YSU?

Sherry: Sure. Every now and then I get to teach a class on Youngstown, which is very cool cause we let people understand, you know, that landscape that they’re driving by every morning not very often. I do a lot of upper division literature courses that on the surface do not connect with this other side of my life but I also teach in the graduate program in American Studies. We have a whole cluster of courses on Working Class Studies. So, I get to teach a course called Class and Culture that talks about… first of all, the idea that working class is a cultural category, not just a socioeconomic one, but also talks about the intersections of class with other cultural categories, with race, with ethnicity, with sexuality, and talks about cultural representations of class, so we do a lot of study of pop culture in that course. I teach a graduate course on working class literature where we get to read all kinds of things that we’ve been talking about. We read Patricia Dobler and others. Also a heck of a lot of fun. I also get to teach a course that, um… I don’t know how to explain how it fits in. We have a course in the graduate program in American Studies called Humanities in the Community which sounds really vague. What it’s all about is teaching students about community organizing, teaching them about how to create public humanities projects, so, how to do something like form a magazine… how to write grant proposals so you can get money for the things that you want to do, how community organizations operate. And I love that class because it’s one of… I feel like one of my missions is to help students think beyond “I love literature, I love popular music, I love all this stuff, I want to study it for the rest of my life,” to thinking about how they can be actors in shaping the community and changing the community, that there’s a value in that knowledge that we try to convey of the humanities that is actually practically useful on the streets of this community. And so, when students in that class are volunteering with the Mahoning Valley Organizing Collabrative, they’re working with the children’s museum, they’re working with the steel museum, they’re working with… you know, I had somebody in that class a few years ago, they do some field work. He did his field work on a political campaign. This makes me very proud and very happy (laughs).

Chris: Good, good! (laughs). Well, Sherry, this has been great. Thank you very much for the interview.

Sherry: You’re very welcome.

Chris: To everyone listening – we hope you enjoyed this. You can visit the Center for Working Class Studies online at cwcs.ysu.edu. You can find information there about the Center’s current projects as well as a working class perspectives blog, resources for teaching about class, and much more. Steeltown USA is available online and in bookstores now.

“Once the symbol of a robust steel industry and blue-collar economy, Youngstown, Ohio, and its famous Jeannette Blast Furnace have become key icons in the tragic tale of American deindustrialization. Sherry Lee Linkon and John Russo examine the inevitable tension between those discordant visions, which continue to exert great power over Steeltown’s citizens as they struggle to redefine their lives.

“Once the symbol of a robust steel industry and blue-collar economy, Youngstown, Ohio, and its famous Jeannette Blast Furnace have become key icons in the tragic tale of American deindustrialization. Sherry Lee Linkon and John Russo examine the inevitable tension between those discordant visions, which continue to exert great power over Steeltown’s citizens as they struggle to redefine their lives.

When ‘the Jenny’ was shut down in 1978, 50,000 Youngstown workers lost their jobs, cutting the heart out of the local economy. Even as the community organized a nationally recognized effort to save the mills, the city was rocked by economic devastation, runaway crime, and mob scandal, problems that persist twenty-five years later. In the midst of these struggles the Jenny remained standing as a proud symbol of the community’s glory days, still a dominant force in the construction of both individual and collective identities in Youngstown.”

-University Press of Kansas